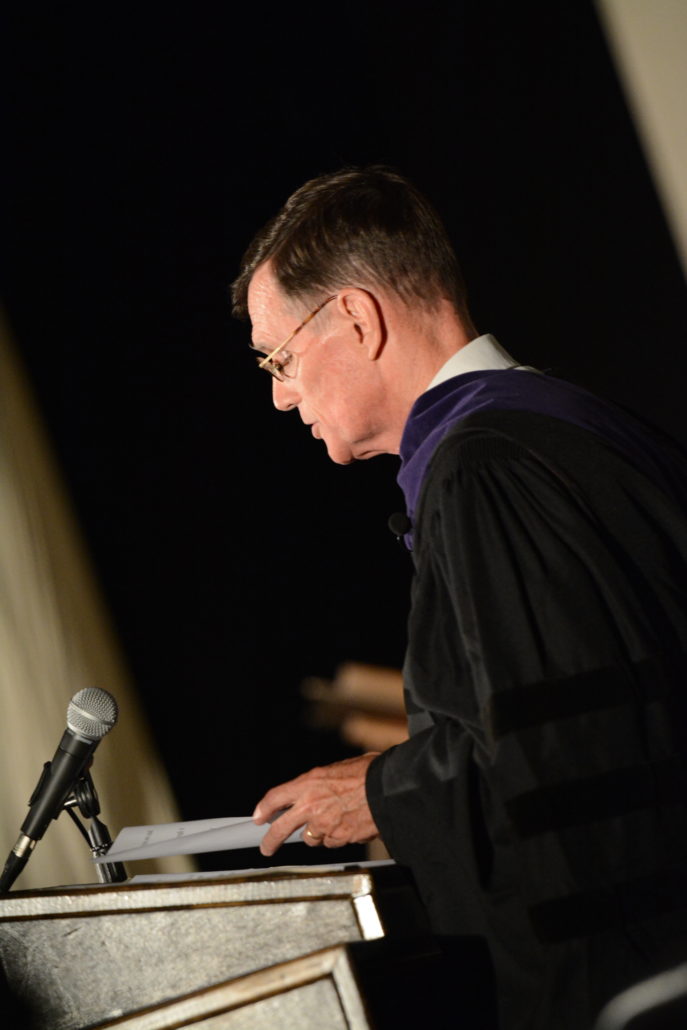

Reflections on Classical, Christian Education: An Interview with Gordon Zubrod

What kind of impact can a classical education have on a person’s life? We recently asked Gordon Zubrod to share his thoughts about how his own classical education served him through his life as a Captain in the Marine Corps and federal prosecutor. As the grandparent of three Covenant alumni, as well as the father-in-law of Covenant’s founding Headmaster, Mr. Zubrod has seen firsthand the impact that a Covenant education can have on students.

Tell us about your educational background.

My undergraduate degree was taken at Coe College in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. I received a Bachelor of Arts in English Literature with a minor in political science. I took my law degree at the University of Maryland School of Law and later graduated from the Naval Justice School in Newport, Rhode Island, qualifying me as a Judge Advocate General in the U.S. Marines.

What (and who) were some of the formative influences on your life?

Key formative influences include, first and foremost, coming to faith in Jesus Christ. I slowly went from a self-absorbed scholar-athlete-reprobate to a simple believer who realized that God had given me a mind and that I should be brave enough to use it in his service.

Second was/is my wife, who showed me what grace looked like at ground level: humble, kind, persevering and ready for laughter.

Third was my father, who read great literature to me from childhood (the Iliad and the Odyssey, Robert Louis Stevenson’s adventures, Kon Tiki, Two Year Before the Mast, countless poems). He even sang. He was called the Father of Cancer Chemotherapy, responsible for developing numerous drugs that retarded or destroyed cancer cells. His faith informed everything that he did. He was offered the Deanship of Georgetown Medical School and Chief of Research for a major drug company after he left federal government (he was chief of scientific research at the National Cancer Institute), choosing instead to work with Haitian refugees in Miami, many of whom were suffering from AIDS. As a marine biologist (his other career), he taught me the Latin names of fish that were being studied at the laboratory in Maine where we spent our summers. When I would correctly identify a species as “squalus acanthius” or “lophius piscatorius” he would bestow his ultimate commendation: “Good show, old man.” By the way, Dad told me that his most significant training for medicine was Latin and Greek, which taught him the mental structure to see the essential “grammar and logic” of cell structures and of the diseases that attacked those cells.

I should add my long-suffering mother, who made me recite poetry and the rules of grammar to her each night as she prepared dinner and who persevered in prayer for me during the lost years.

The Marine Corps was an astringent application of discipline and method. I learned structure, chain of command, to take on large responsibilities and develop a bias for aggressive action regardless of the odds against me. They also required us to take the most difficult tasks (including examinations) when we had gone weeks without adequate sleep, food or preparation. The key was to find out who could perform best when he felt he had nothing left. It left a strong impression to this day, having become the habits of a lifetime.

I was greatly influenced by the Benedictine monks, who taught me for four years as a teenager (at St. Anselm’s Abbey in Washington, D.C.). I became what my daughter refers to as a “grammar Nazi.” They made us read difficult texts, including Caesar’s Gallic Wars, Virgil’s Aeneid and other Great Books. Mostly, I was struck, not only by how learned they were, but how reflective and thoughtful they were. Indeed, my wife and I still speak French to each other when the topic is sensitive and the grandchildren are around.

Finally, a very great influence was books. My mother, during the summer months, required us to read for two hours every day after lunch. Four of the five of us (the fifth was way too young) would climb into the same giant hammock and read each day. I read my way through the children’s and the young adult sections of the library in Bar Harbor, then walked into the adult section and discovered mysteries, which directed my career choices. A near disaster occurred when I asked my mother what a “lingerry” was. When, after making me spell it and discovering that the word was “lingerie,” she began to censor my reading choices. That incident led me to look up words for myself in the dictionary. I am still a bookworm, and still looking up words on my own.

How did your classical education impact you?

Classical education affected my life as a Marine and as a Federal prosecutor in a number of ways. I learned to read texts (orders, battle plans, statements, case law and facts) very carefully, to ask pointed questions based upon my reading of the facts and the law and to disagree with particularity and force when I thought a superior was wrong. I learned that huge issues and contests are usually decided on very small facts, minute details and to be the most versed on these facts going into any conflict or debate.

My classical education also trained me in the art of persuasion, to find le mot juste to deploy with skeptical agencies, autocratic superiors, aloof judges and in negotiating with brilliant opponents. Once, a barrister from Canada wrote me a letter about my position. He quoted Swift: “It is a wonderful thing to be a giant, but a terrible thing to act like one.” (Gulliver’s Travels). After laying out the ruin caused by his client to innocent people, my closing response was borrowed from Pepys: “A scoundrel’s back should taste the lash.” Great fun. Moreover, throughout my career, I have done the essential writing in every case that I have handled. Others may tweak the draft, but the essential text is mine. Having written the core documents, I was also the most informed and best prepared to try the case. It was a telling advantage.

Finally, in the legal profession, I came across numerous men and women who had a similar love for the law as a profession and were engaged in a life-long pursuit of self-education. They were well read in history, literature, philosophy and, of course, the law. In the midst of conflict and strife, they would reach back for a classic quote (e.g., “Once more into the breach…or else fill up the wall with our English dead.”).

You recently taught Covenant’s first ever Moot Court elective along with U.S. attorney, and Covenant parent, Stephen Cerutti. What are some of your observations?

Steve and I approached the course with some foreboding, not knowing how well the students would grasp complex Constitutional issues, rules of evidence, how well they would be able to handle oral argument and the think-on-your-feet give and take of the courtroom. We needn’t have worried. They were very sharp and, for the most part, took the course very seriously. Of course, some were superior and their preparation made them stand out when they rose to present their case to the Court. As a teacher, I found that the greatest quality of the students, in addition to their ability to grasp complex ideas, was their intellectual curiosity. I was continually challenged on the justice or logic of a particular Supreme Court ruling. The debates would rage between students on a particular issue or legal precept, with each combatant clearly expressing his/her position. Again, for the most part, they were not afraid of work, which included weekends and after-school hours. They wanted to get it right.

Were your goals for the course achieved?

On the positive side, the students rose to a high standard. As one expressed it in a letter written after the trimmest had ended, she had not realized how hard it was to become competent in a profession and how thrilling it was to find herself moving toward it after much effort. Several students said that the experience whetted their appetite for law and were considering pursuing a professional degree.

On the negative side, I think that we should have allowed more time for oral argument during the semester, but were hindered in doing so by the volume of information that had to be absorbed in order for the students to competently argue their cases in Federal court.

What advice would you give to parents considering coming to (or staying at) Covenant?

As the grandfather of three alumni of Covenant, I can personally testify to the performance of the school’s graduates in college and grad school. Zoe graduated summa cum laude from both Grove City (BA) and Villanova (MA). Noah, who will be entering his senior year, is carrying a 4.0 average in philosophy and is heading to Oxford to study philosophy and then to Italy to study Latin for a year. Moreover, their former classmates have experienced similar success in college. I was talking to a graduate of Covenant last Sunday. He told me that his college classmates were terrified of having to prepare a 5-minute presentation in Speech class. He stated that he had done it so frequently that he didn’t even break a sweat in his presentation, which was head and shoulders above the other speeches.

I’m not certain of the precise makeup of the final years at Covenant, but I am aware of the Senior Thesis and I presume that there is greater freedom in the final years to experience the professions. If not, I would include visitors from the professions, chosen for their ability to communicate the particulars of professional practice. This would include college professors to alert students what to expect when they get to college. Perhaps, visits to a medical school, a college class or a business (such as Classical Academic Press) would add to their experience as a Covenant student. I also think that debating, public speaking or dramatic readings of plays and even acting out parts of plays should be a requirement of the rhetoric phase (in college, we used to get together with some of our professors and read portions of plays, always the high point of the week).

In any case, those are the things that I would offer to parents, namely, that an upperclassman at Covenant gets to do things that most people experience only (and even then, rarely) in college. In other words, the school is not just about getting the necessary number of courses to graduate, but to experience the love of learning, becoming a lifelong learner along the way.

Thank you, Mr. Zubrod, for sharing your thoughts with us!